Learn About Exploration

Why & How We Find Copper

Copper deposits are relatively rare in Earth’s crust. Exploration geologists combine:

- Literature & historical records

- Surface rock observations and mapping

- Mineralogical clues (veins, gossan)

- Geophysical surveys for buried anomalies

Discuss: What rock types and textures might signal a porphyry copper system?

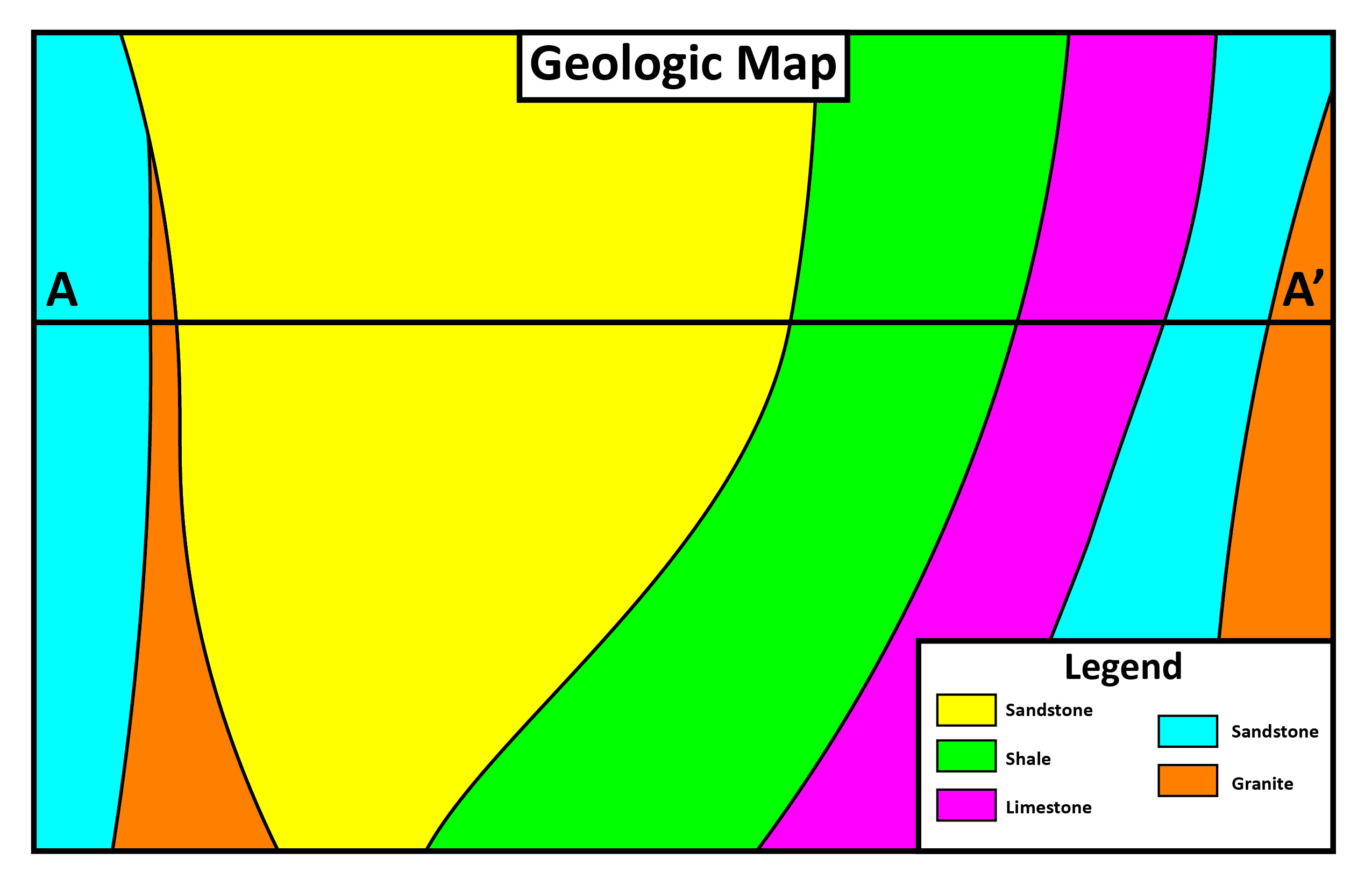

Geologic Mapping & Porphyry Textures

Arizona’s porphyry copper deposits are associated with coarse‐crystal granite (“porphyryt ic”). Geologists:

- Identify porphyritic outcrops

- Map distribution of host lithologies

- Collect rock samples for lab analysis

Hands‑On: Examine a porphyry sample—spot large feldspar phenocrysts vs. fine matrix.

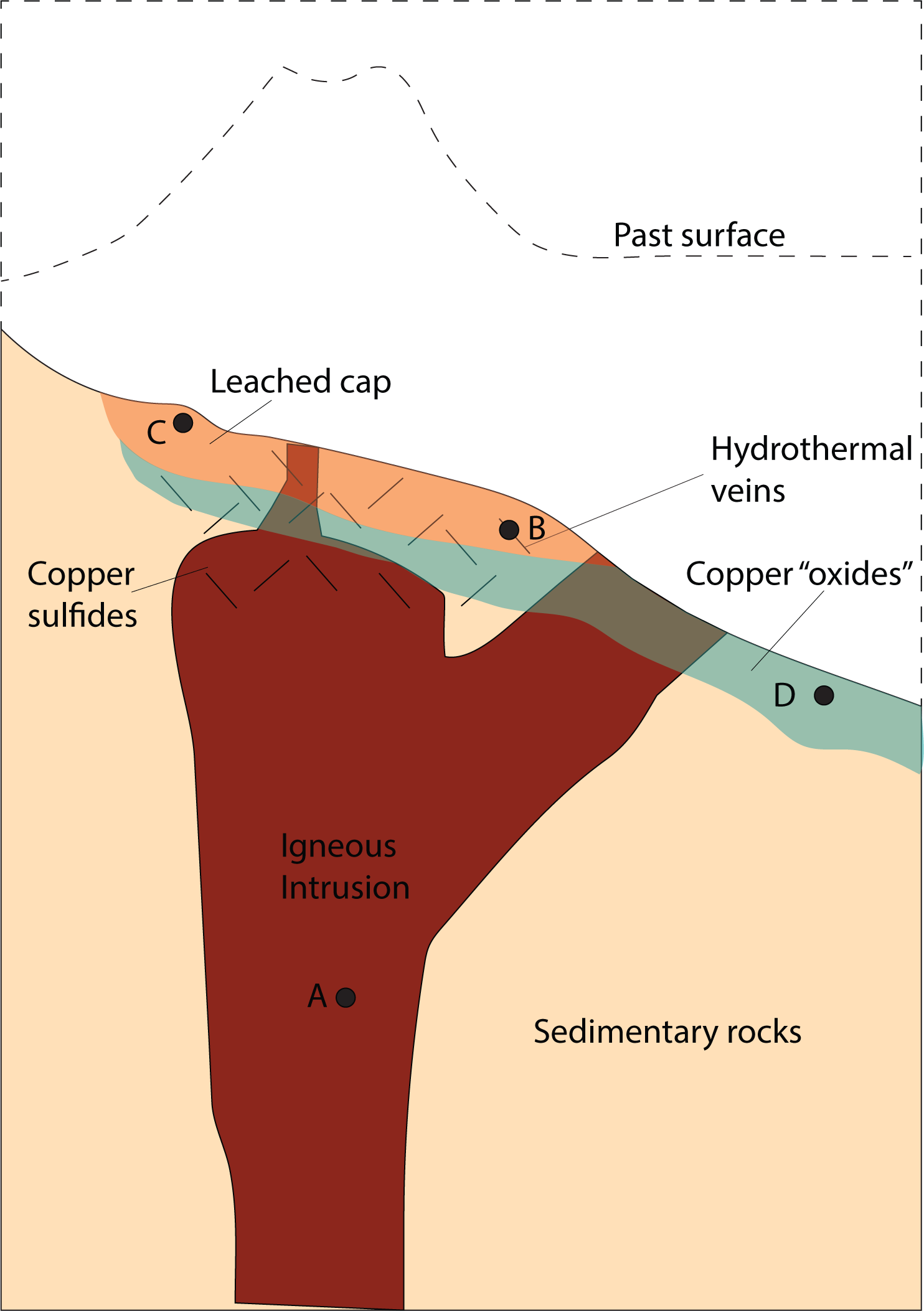

Veins, Pyrite & Gossan

Hydrothermal fluids travel along fractures, depositing copper minerals (e.g., chalcopyrite) in veins. Sulfide minerals (pyrite) at surface oxidize to form gossan:

- Rust‐colored cap from weathered pyrite

- Indicator of deeper sulfide zones

- Acidic fluids can leach and transport copper → secondary oxides

Observe: Compare chalcopyrite‐rich vein vs. oxidized gossan outcrop.

Seeing Below the Surface: Geophysics

Surface mapping reveals only the top few meters. To explore deeper (up to 1 mile), geologists employ geophysics:

- Magnetics: Detect variations in rock magnetic susceptibility

- Induced polarization: Measure charge build‑up in mineralized zones

- Seismic: Image subsurface layering via sound waves

Demo: A buried magnet test in a plastic box—run a handheld sensor to locate the anomaly.